Anyone who goes up to the acropolis of Tel Azekah sees below it, towards the north and the west, a flat and straight mound, like a football field. There are no such things in nature. Someone worked hard to create it based on the natural, rounded hill that was there before. How did this happen? Many years of excavation at the Tel has revealed some of the secrets of the process and the periods in which it happened.

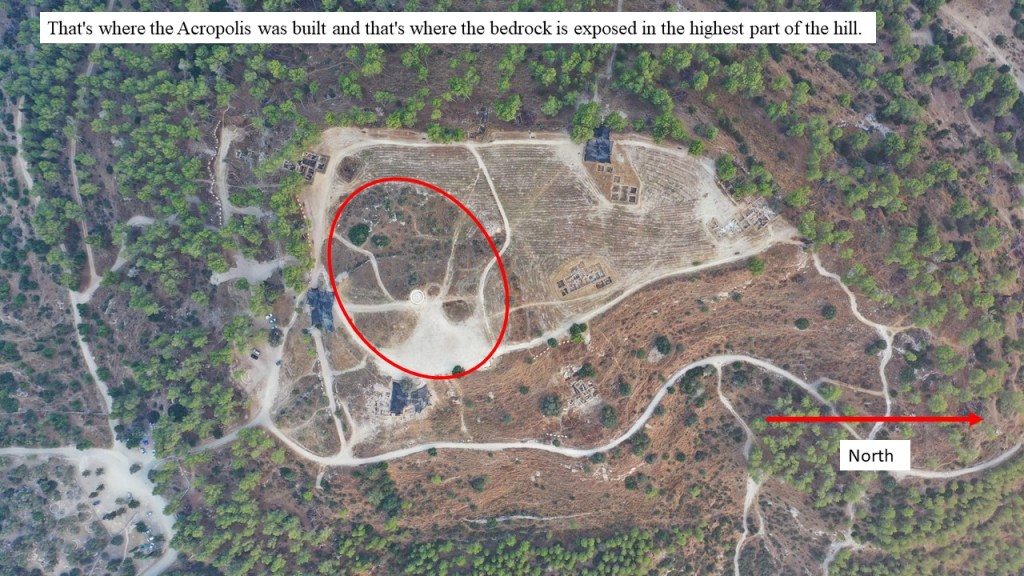

The top of the original hill on which Tel Azekah was built was in the area that is today the southeastern part of the mound.

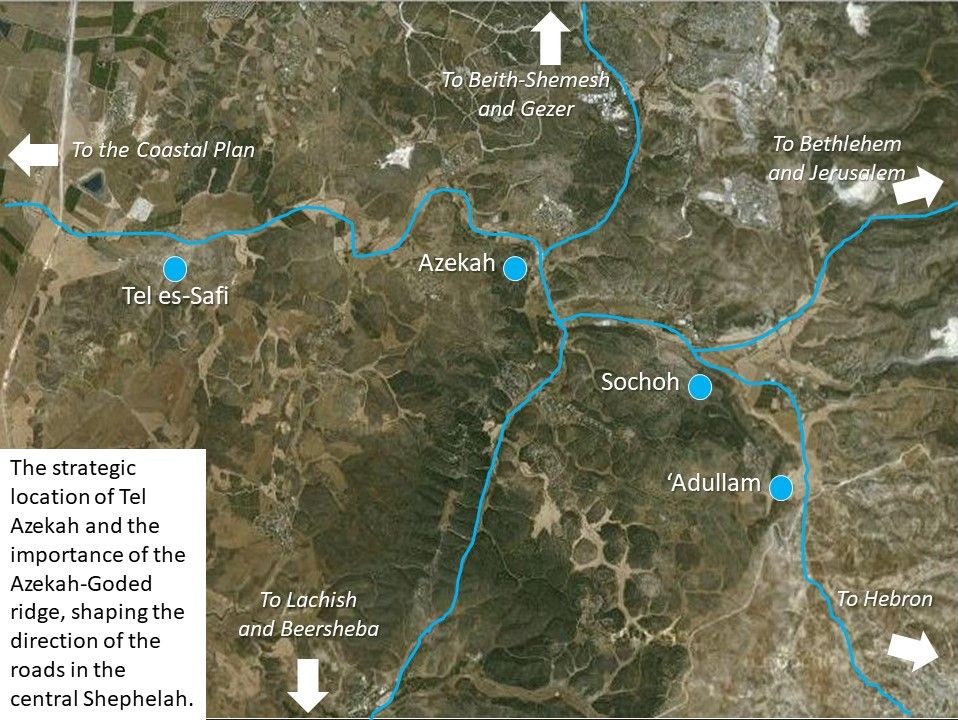

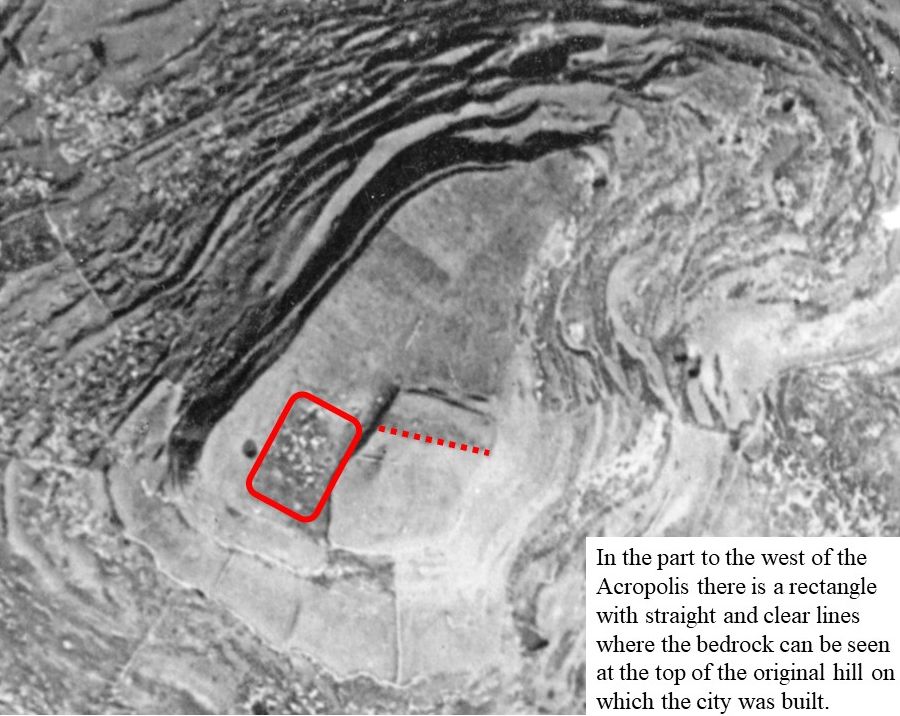

The Acropolis was built on its highest part. To the west of the Acropolis, there is a large area where the natural bedrock is visible. It is reasonable to reconstruct the original top of the hill under the acropolis and on the exposure of the bedrock to its west. It seems that from this area the hill sloped sharply to the south, towards the natural saddle that connects Azekah to the Azekah-Goded ridge.

From this area, the mound also sloped sharply to the west, since the rocks which face to the west and the southwest are 11-14 m lower, located at the edge of today’s mound.

From this area, the mound also sloped northward, apparently in a more moderate manner, towards the area that is today below Area N, where the bedrock was exposed along the step above Area G.

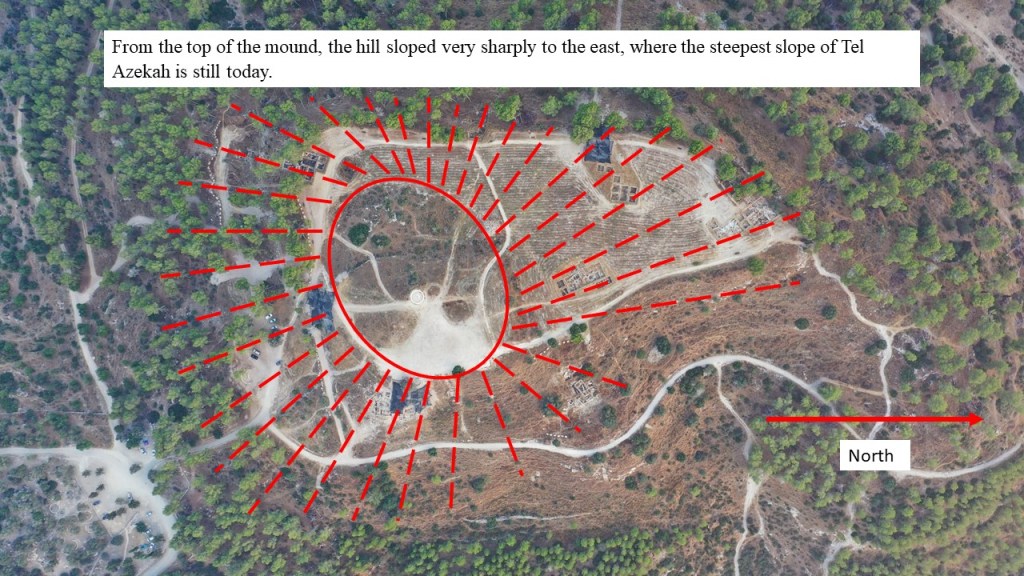

From the top of the mound, the hill sloped very sharply to the east, where the steepest slope of Tel Azekah is still today.

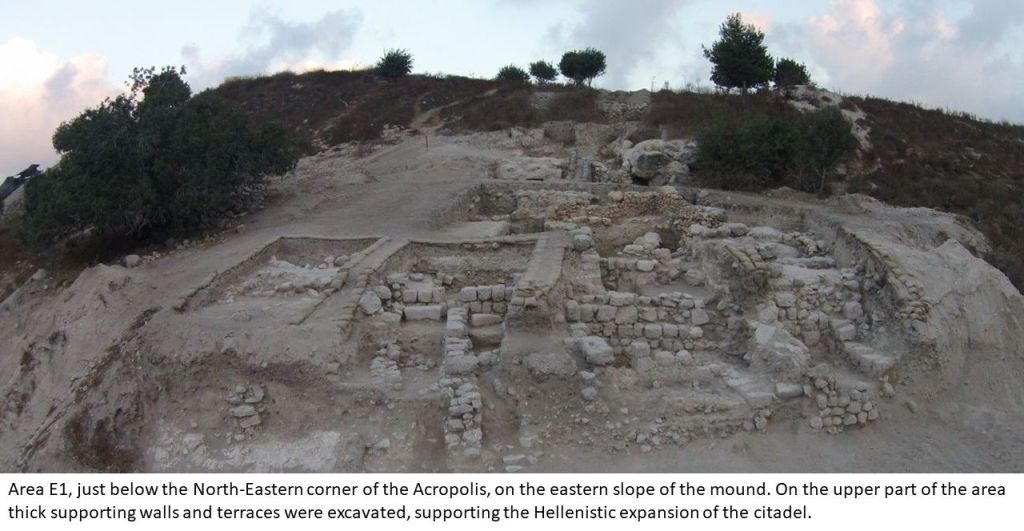

From the level of the Middle Bronze Age fortifications and the Late Bronze Age temple that were uncovered in area E1, it is clear that the top of the hill in those periods was about 7-10 meters lower than where the top of the Acropolis is today.

The end of the process of the creation of the mound was in 1899 when Bliss and Macalister covered the area that they excavated and brought it back to the landowner in the same condition they received it.

However, when the Acropolis was built in the Iron Age, and then during the Hellenistic period, supporting walls and thick terraces were erected in the eastern part, and they supported the massive fills in the eastern steep slope. The natural slope of the mound towards the east became even steeper, and the citadels that stood at its top for hundreds of years were built in its most strategic and commanding area, facing the Ellah Valley, the hill country to the east of the valley and the north-south road that passed below the Azekah–Goded ridge.

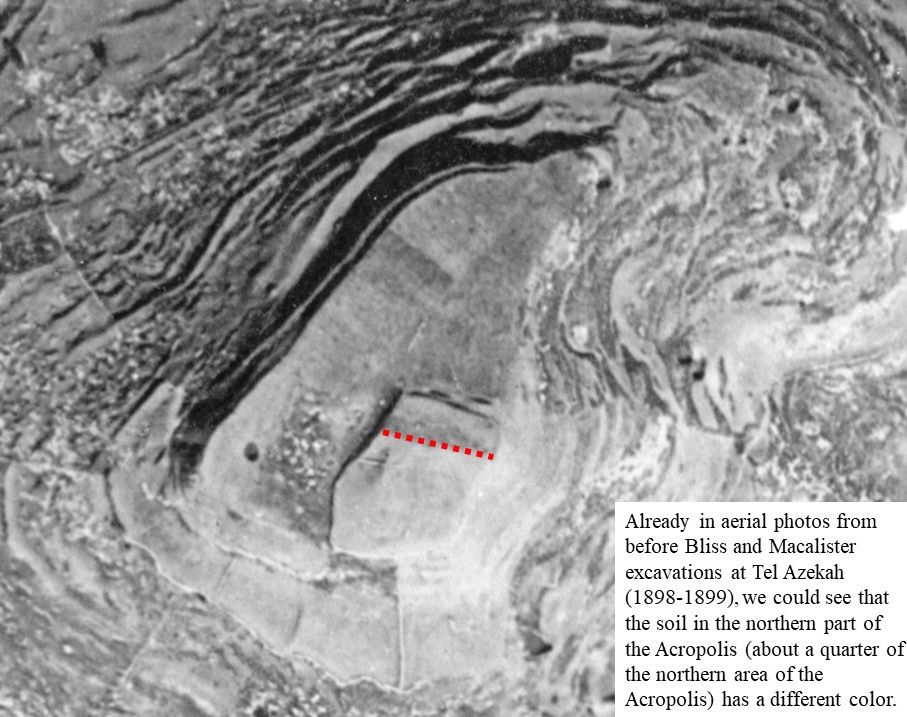

In aerial photos from before Bliss and Macalister’s excavations at Tel Azekah (1898-1899) we could see that the soil covering a quarter of the northern part of the Acropolis has a different colour.

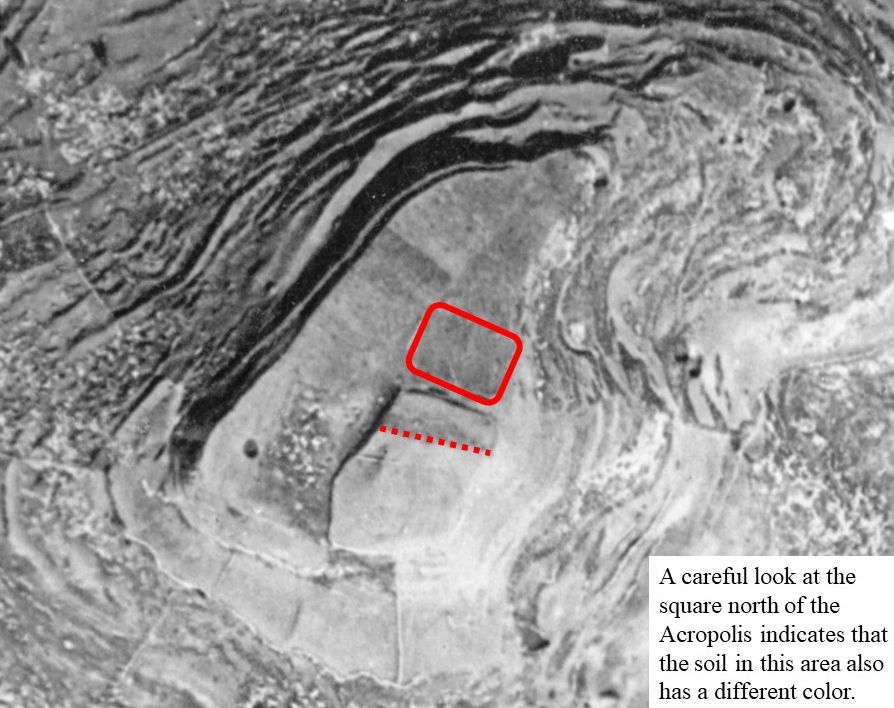

A careful look at the square north of the Acropolis indicates that the soil in this area also has a different colour. In the west of the Acropolis, at the top of the original hill on which the city was built, there is a rectangle with straight and clear lines where the bedrock can be seen.

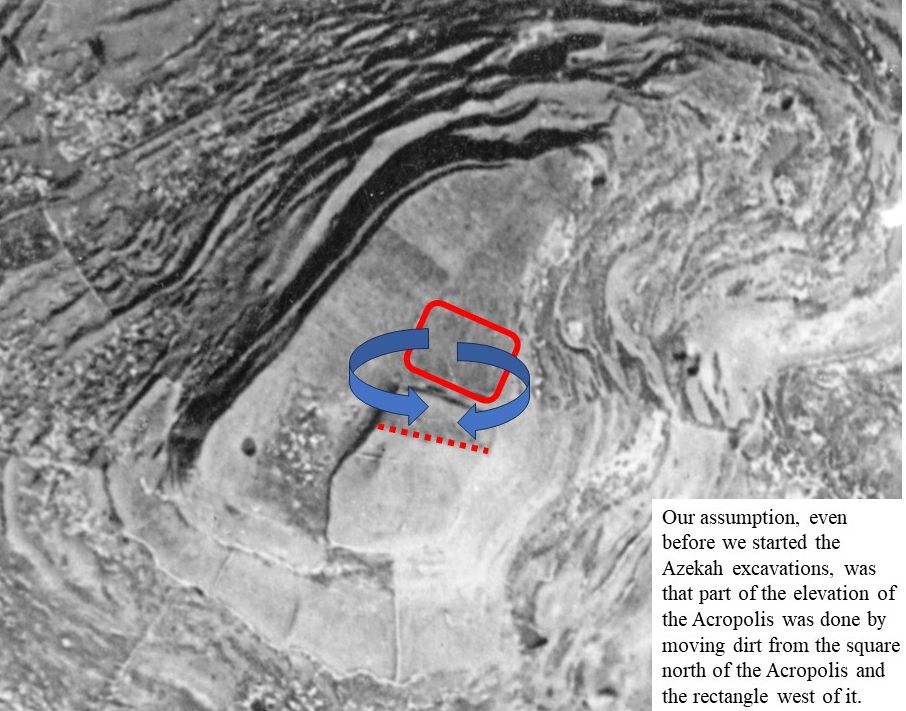

Our assumption, even before we started the Azekah excavations, was that part of the elevation of the Acropolis was done by moving dirt from the square north of the Acropolis and the rectangle west of it.

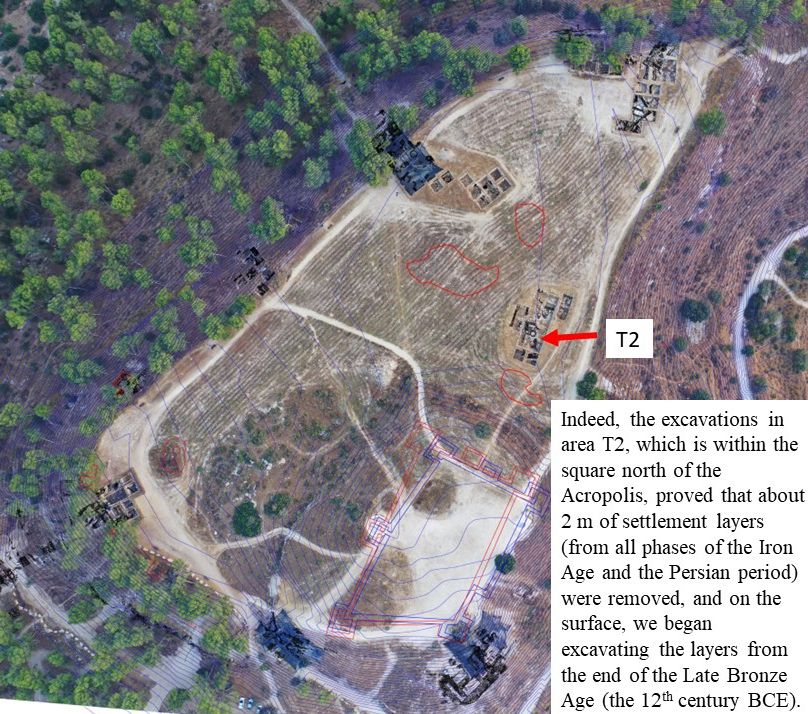

Indeed, the excavations in area T2, which is within the square north of the Acropolis, proved that about 2 m of settlement layers (from all phases of the Iron Age and the Persian period) were removed, and on the surface, we began excavating the layers from the end of the Late Bronze Age (the 12th century BCE).

Interestingly, about 50 m west of area T2, in area T1, the missing 2 m of Iron Age and Persian period layers were found at the same level.

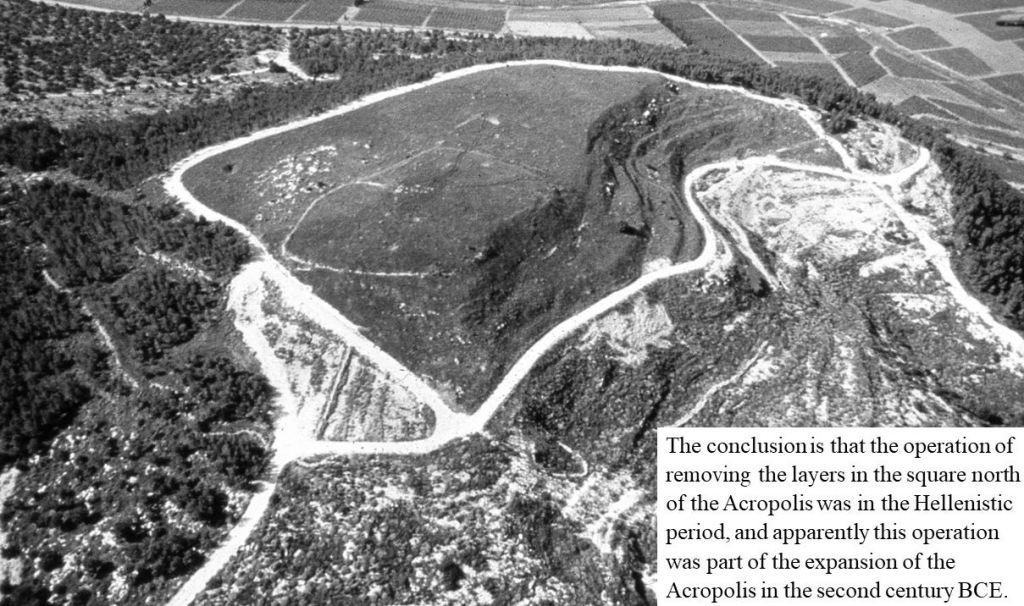

The conclusion is that the removal of the layers in the square north of the Acropolis was conducted in the Hellenistic period, and apparently, this operation was part of the expansion of the Acropolis in the second century BCE.

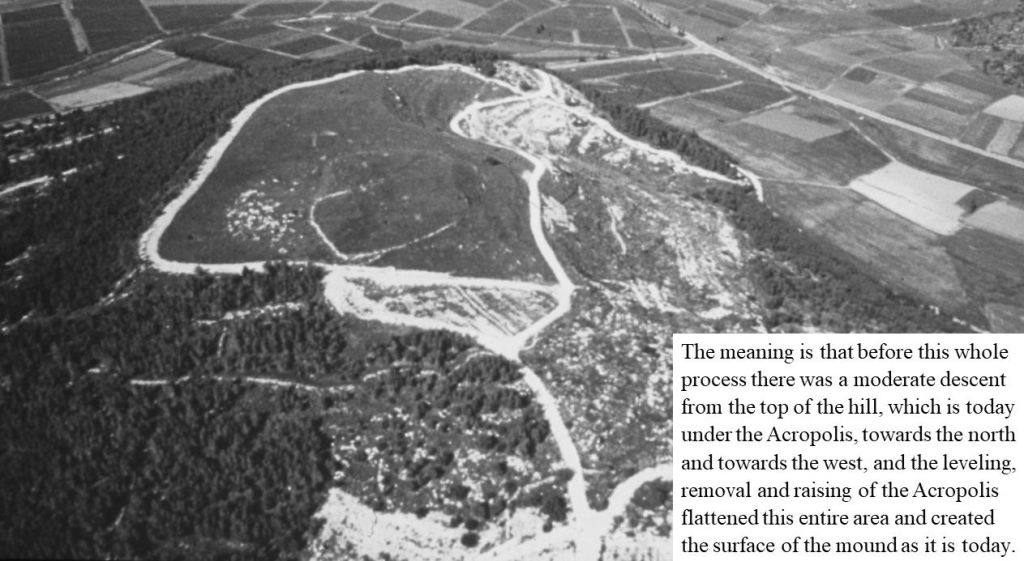

The meaning is that before this whole process began, there was a moderate descent from the top of the hill, which is today under the Acropolis, towards the north and the west, and the raising of the Acropolis by removal of soil from these areas flattened it and created the surface of the mound as it is today.

This was probably the last step in the process of “flattening” the mound, and apparently, as in life – also in history, part of the way to raise one side is to lower the other side…

And what happened west of the Acropolis?

The top of the original hill of Tel Azekah was in the southeast corner of the ancient mound. That’s where the Acropolis was built and that’s where the bedrock is exposed in the highest part of the hill. From the southeastern part of the hill, there was a moderate slope towards the north, a steeper slope towards the west and a very steep slope towards the south and the east.

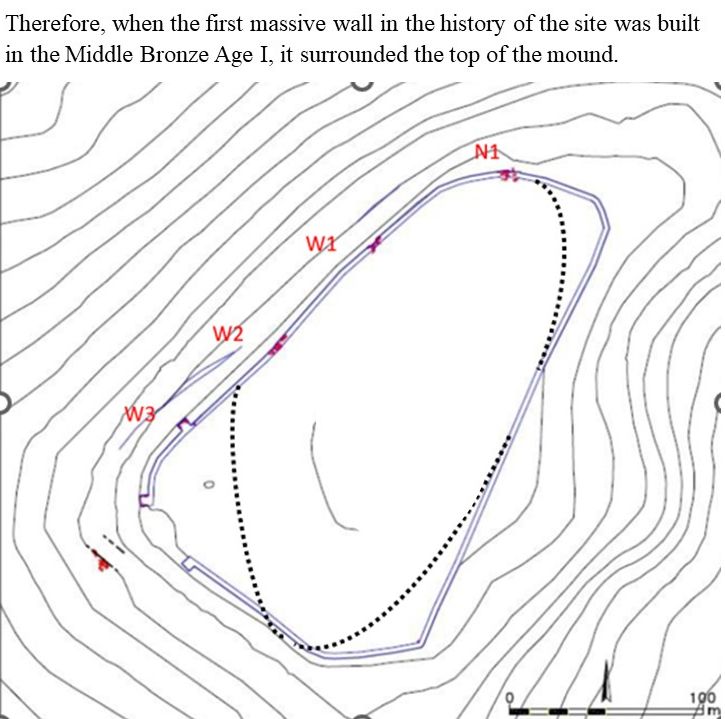

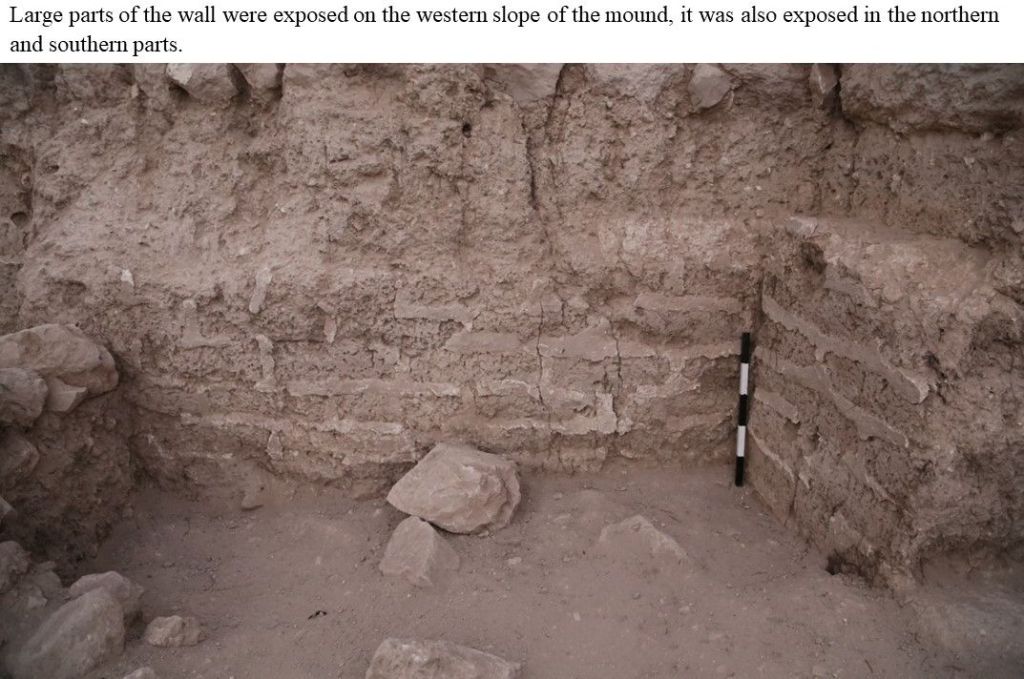

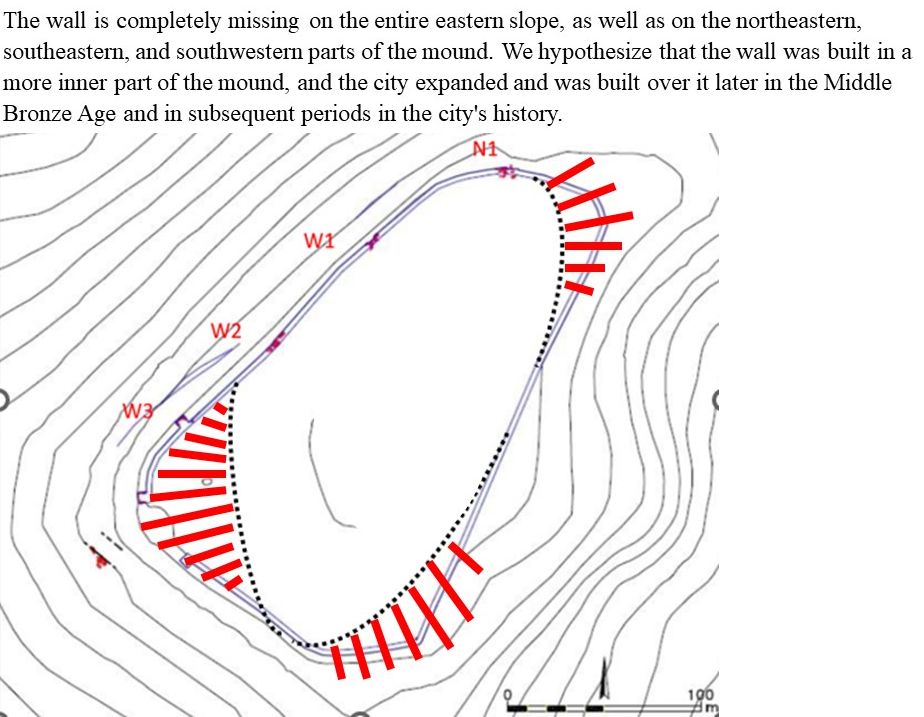

Therefore, when the first massive wall in the history of the site was built in the Middle Bronze Age I, it surrounded the top of the mound. Large parts of the wall were exposed on the western slope of the mound. The wall is completely missing on the entire eastern slope, as well as on the northeastern, southeastern, and southwestern parts of the mound.

We hypothesize that the wall was built in an inner part of the mound, and the city expanded and was built over it later in the Middle Bronze Age and subsequent periods of its history.

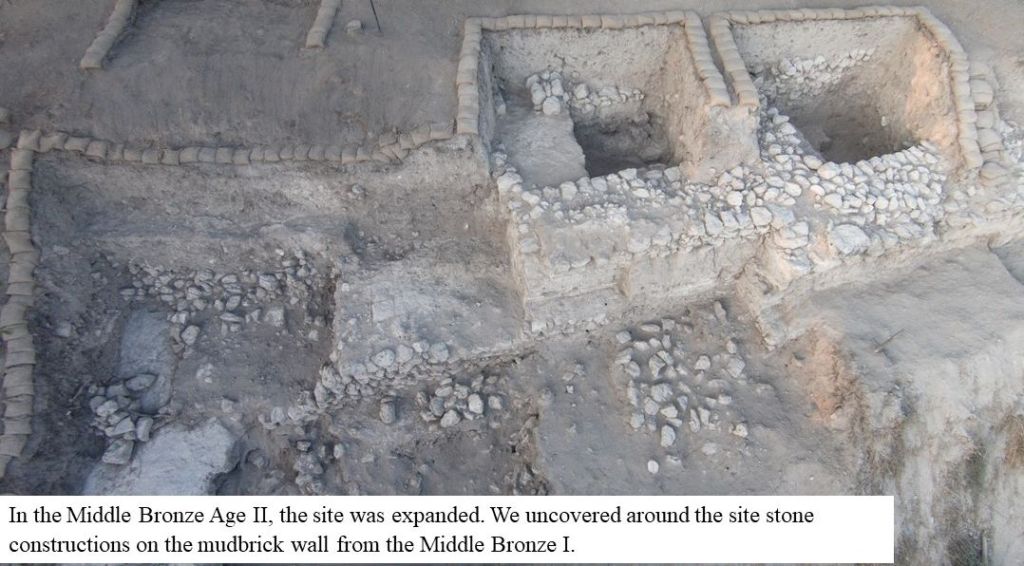

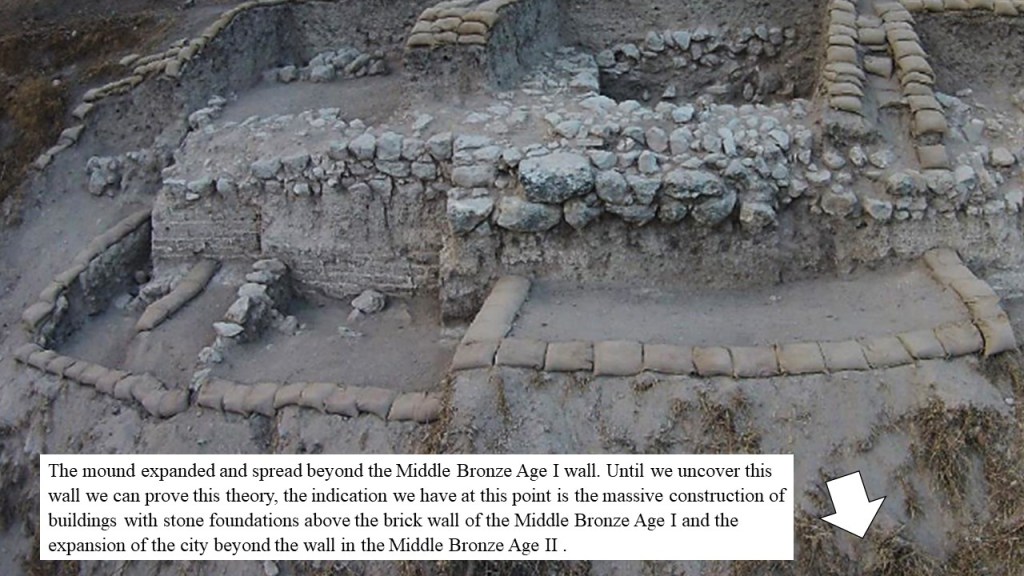

The mound expanded and spread beyond the Middle Bronze Age I wall.

At this point, until we uncover this said wall, the indication we have is the massive construction of buildings with stone foundations above the brick wall of the Middle Bronze Age I and the expansion of the city beyond the wall in the Middle Bronze Age II.